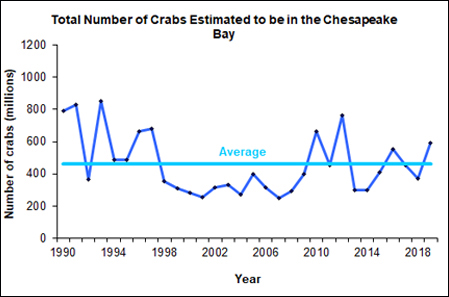

Blue crabs, the icon of Chesapeake Bay, reached a tipping point in 2008. After 16 years of almost nonstop decline, populations had plummeted to little more than a third what they were before. Officials declared the fishery a federal disaster. Now populations are slowly climbing back. But it’s a fragile recovery. A slight upset in the wrong direction could send them back downward—and with them, the livelihoods of watermen who rely on the Bay for their daily bread.

Total blue crabs estimated in Chesapeake Bay since 1990, according to the annual Winter Dredge Survey. (Maryland Department of Natural Resources)

The crabs’ survival depends on the annual journeys they make up and down the Bay. Marine biologist Tuck Hines has been tracking these journeys for more than 30 years.

Marine biologist Tuck Hines.

Every year, female blue crabs migrate to the mouth of Chesapeake Bay to hatch their eggs. It is a journey fraught with peril. On the way, they must survive freezing winter waters (usually by burrowing into the mud) and avoid the nets and traps of fishermen. If they don’t make the journey to saltier waters, the millions of eggs they carry under their abdomens will fail to hatch or die.

At the same time, many juvenile crabs migrate upstream. They face dangers of their own—not from nets, but from their own kind. Cannibalism isn’t uncommon in the animal world. The biggest threat to young blue crabs comes from adult blue crabs looking for a quick meal. Most will not survive past the juvenile stage. The ones that do will look for mates in the Bay’s fresher tributaries and begin the cycle again. Ideally, enough will survive to replenish the fishery for the crabbers who make their living on the water, and the seafood packers and restaurant owners ashore.

But finding the right balance can be difficult. It takes more than knowing how many crabs are in the Chesapeake. For Hines, it comes down to knowing where they are, where they feed and molt, and when they begin their migrations.

His team has come up with several creative ways to track them. They’ve tagged adult crabs and enlisted watermen to report where they’re caught. A more high-tech experiment released hatchery-bred juveniles with microwire tags into the Bay. They’ve even taken apart crab shells to see if different parts of the Bay leave their own chemical fingerprints. Beyond that, they have spent three decades doing regular trawl surveys on boats and setting up fish weirs in Chesapeake rivers to monitor the creatures that pass through.

The crab population crash that began in the early 1990s offers a stark picture of a fishery out of balance. By 2000, the number of mature females in the lower Bay had fallen 84 percent. Meanwhile prices skyrocketed above $300 a bushel, and the Chesapeake resorted to importing crabs from other states, and even crab meat from species in southeast Asia. Then, in 2008, Maryland and Virginia both took steps to protect adult females. Two years later the population rebounded.

Biologists, watermen and policymakers now face the task of keeping the recovery going. No one wants to see the traditional life of the Chesapeake crabber fall away. How much shielding blue crabs need, and for how long, are questions only good data can answer.

Learn more about SERC’s blue crab research at the Fish and Invertebrate Ecology Lab and the Fisheries Conservation Lab.