More than 200 species of orchids blossom in North America. Their names are as mesmerizing as their flowers: Dragon’s mouth. Threebirds orchid. Yellow lady’s slipper. But unlike their showy cousins in the tropics, the orchids of the temperate zone often flower unseen. More than half are endangered or threatened somewhere in their native range.

This video tells the story of one, the small-whorled pogonia Isotria medeoloides. Once commonplace, Isotria is now considered the “rarest orchid east of the Mississippi.” It has already vanished from Maryland and is endangered in 16 of the 20 states where it remains. SERC ecologists are attempting to bring it back. The mission requires them to piece together a much larger puzzle connecting orchids, microscopic fungi and the roots of trees underground.

This video tells the story of one, the small-whorled pogonia Isotria medeoloides. Once commonplace, Isotria is now considered the “rarest orchid east of the Mississippi.” It has already vanished from Maryland and is endangered in 16 of the 20 states where it remains. SERC ecologists are attempting to bring it back. The mission requires them to piece together a much larger puzzle connecting orchids, microscopic fungi and the roots of trees underground.

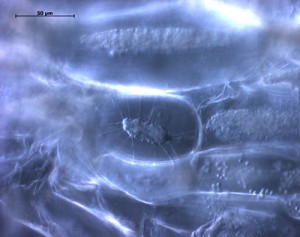

To survive, orchids depend on mycorrhizal fungi—fungi that interact with the roots of plants and help them take up nutrients from the soil. Orchid seeds start out as tiny, wind-borne particles barely the size of dust grains. These “dust-seeds” are too small to supply their own nutrients. To germinate and grow, an orchid seed needs to land on moist soil with just the right fungus nearby. Its relationship with the fungus enables the orchid to grow into a microscopic protocorm, and later grow into a seedling. Gradually the fungi start to penetrate its cells and form coils of hyphae called pelotons. Orchids digest these pelotons to obtain the nutrients they need for growth.

View the complete life cycle of an orchid >>

Protocorms, the second stage of an orchid’s life cycle. Once orchid seeds find a fungus they are compatible with, they can germinate into microscopic protocorms like these of the rattlesnake plantain. Some protocorms remain below ground for years before producing their first leaves.

As the orchid grows into a seedling, the fungi form coiled bundles called pelotons inside its root cells. The orchid cell in this photo has already partly digested its peloton (dark clump in center). The tubes radiating out carry products from the digested peloton to the plant.

But there’s a catch: Not every mycorrhizal fungus will work. Each orchid species has a different set of fungi that will enable it to grow and survive. So far scientists have found only six closely-related fungi that work for Isotria. Some orchids interact with only one. This fact makes them incredibly vulnerable to change.

Meanwhile, as the orchids depend on fungi, the fungi that Isotria needs depend on trees. Many of the fungi orchids rely on thrive in older forests. In Maryland, Isotria’s fungi interact with the roots of oaks, hickories or beeches—trees that may not appear until a forest is 100 years old. If a forest is cut down, different trees rise up to replace the old ones. It may take decades or centuries for the orchids that once blossomed there to return, if they return at all.

Meanwhile, as the orchids depend on fungi, the fungi that Isotria needs depend on trees. Many of the fungi orchids rely on thrive in older forests. In Maryland, Isotria’s fungi interact with the roots of oaks, hickories or beeches—trees that may not appear until a forest is 100 years old. If a forest is cut down, different trees rise up to replace the old ones. It may take decades or centuries for the orchids that once blossomed there to return, if they return at all.

Orchids are fragile plants. Because of their dependence on fungi, any change in the soil can threaten their survival. But their fragility also makes them powerful allies. Like canaries in a coal mine, orchids offer a clear picture of a forest’s health. Their presence indicates that the forest is in good shape. Their disappearance can send up an early warning that something is wrong. The decline of Isotria could be a small reflection of a larger issue in the forests of eastern America. And so the quest to save Isotria, and all orchids, becomes a quest to save an ecosystem.

Learn more!

Find more about SERC’s work to conserve orchids in the Molecular Ecology Lab and the Plant Ecology Lab. Explore native orchids across the continent at the North American Orchid Conservation Center.

Learn about the native orchids in the U.S. Check out the

Learn about the native orchids in the U.S. Check out the